But I Am Living Still

I was a healer I was gifted as a girl I laid hands upon the world

This is a Job for Kool Aid

My little brother and I shared a childhood fantasy. We wanted to set up our own Kool Aid stand at the corner of Linda Sue and Leonard Lane. Oh yeah!

That never worked out. Instead, I mowed lawns with my best friend, Kevin, and sold greeting cards door to door. The American Dream. I wrote stories and knocked on doors selling Mason Shoes. My brother grew up, joined the Navy, and eventually became co-owner of a steam plant in the Northeast. I took a different path.

Joliet, a river town on the outskirts of Chicago, shaped our early years. I spent my first eight years there, and my brother, his first five. Known as the City of Stone for its limestone quarries, Joliet was also home to a prison and an ammunition factory, a gritty backdrop. The town’s bridges were its landmarks. Every week, I walked across the Jefferson Bridge over the Des Plaines River, clutching my quarter allowance on the way to Woolworth’s. I loved the drawbridge most of all: the groan of steel as it lifted to let ships through, the clang clang clang of the warning signal, the cars and pedestrians forced to pause. For a few minutes, everything stopped.

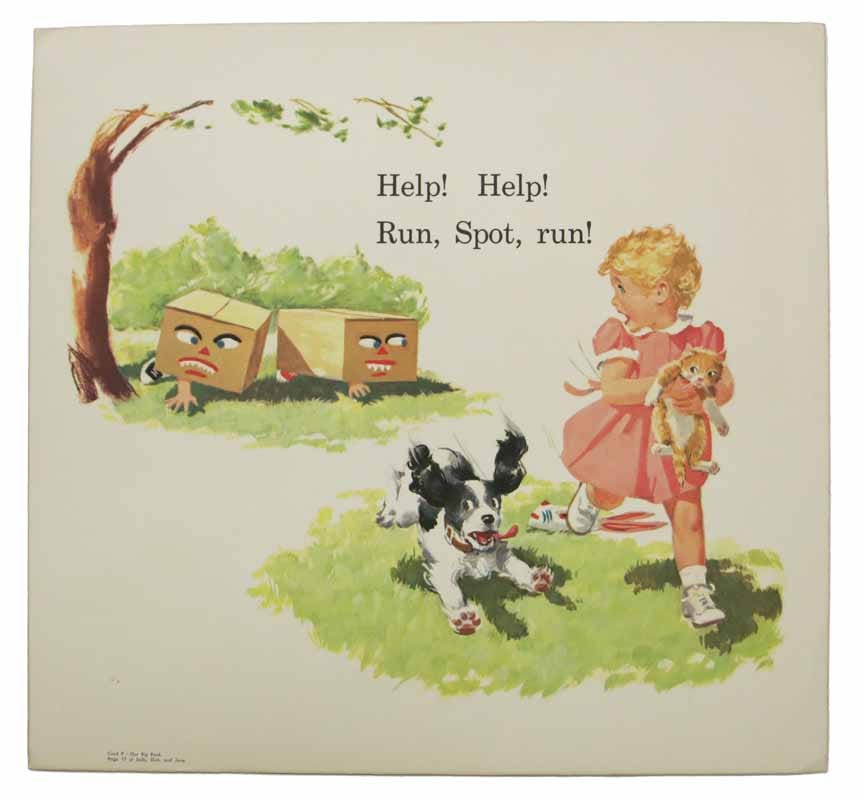

First grade was another kind of pause, permeated by the peculiar dusty-stone smell of chalk, the smooth whorls of the wooden desk beneath my fingers, and the green chalkboards lining the walls. The bluish-grey of a Joliet sky flooded the windows while a large American flag hung in the corner. Beneath it, Mrs. White taught us to read Dick and Jane books. I loved school. Oh, see Jane. Oh. Oh. Jane was wise and big, like my big sister, and Dick was a boy like my brother. I wanted to be Sally but knew that was my baby sister’s slot. See, see, we read. Look, look. But where was I? There was a dog. Our dog’s name was Sandy. The year I was born, 1954, the words “Under God” were added to the Pledge of Allegiance. In 2024, we are making America great again. One day, Sandy disappeared. For years we didn’t know our mother had dropped her off at the dog pound.

We learned the pledge in kindergarten, our right hands pressed firmly on our tiny chests as we fervently pledged obedience. My childhood is a blur of ritual. The bump that grew on my middle finger from gripping the fat pencils and drawing letters on Big Chief newsprint, the love affair I developed with writing, are still there. The darkish red of the tablet’s cover, the outline of an American Indian man in full headdress, etched in my memory next to the red, white, and blue stripes, the star-spangled flag the only bright spot in the dull room; I wanted to eat it. I loved writing my name and the date at the top of the page. Erasing the blackboard and cleaning the eraser were my favorite tasks. I loved banging those two erasers together just outside the classroom door, where we lined up every morning and recess. I loved the smooth lines of lead on the soft paper and reading aloud. I was a good reader, learned over my seven-year-old sister’s shoulder when I was four, almost accidentally. What magic to see the marks on the page come alive with meaning. I was eager to read aloud in the class, raised my hand high, read the words proudly and with feeling. Just like I did when we recited the pledge of allegiance.

In third grade, we learned American traditions and days of observance. Columbus Day. Thanksgiving. Lincoln’s Birthday. Mrs. Branch wrote Today is Groundhog Day on the chalkboard and told us to copy it and write three sentences. I wrote an eleven-page story about a dancing groundhog whose parents forbade her from dancing. A Hollywood agent discovered her and whisked her away. I have no idea where I came up with that since we didn’t have a television, and I’d never seen a movie. But dancing was against our religion. Years later, I took a job as a strip dancer at the Intimate Lounge, where I lasted three days before quitting. Nobody whisked me away. Initially, the Pledge of Allegiance was created to sell flags.

In our two-story home on Irene Street, I watched out my bedroom window mid-afternoons for my father’s return from work, the familiar blue work shirt, Len embroidered over the left front pocket; he was a route salesman for Rainbow bread and kept track of his deliveries in pencil in a brown covered narrow ledger which I envied for its lines and thickness. Our backyard was directly across from St. Patrick’s Cemetery, a graveyard for heathens, for we were taught in the truth,” in home-based meetings we attended twice a week, or weekly gospel meetings in rented school halls, that Catholic priests were wolves in sheep’s clothing. The irony. We were leery of false prophets.

In the meetings, we sat in a loose circle on wooden folding chairs, wooden like the desk I sat in at school, oak and solid, in homes where the head of the household was designated as an honored elder, among them my father, along with an assigned group of saints, or friends, God’s chosen people. We held meetings wherever we lived more often than not. In my earliest memories, I remember those chairs stacked up, initials painted on the back, then arranged in the living and adjacent dining room on Sunday mornings or Wednesday nights.

Sundays after meetings in Joliet, we drove to the tenant farm in Seneca, where my grandparents cared for the livestock, planted and harvested, worked and lived. Dinner was fresh vegetables from my grandmother's garden, mashed potatoes, green beans, peas, roasted chicken, ham, beef, and bread and gravy. As a child, bread and gravy were all I wanted to eat.

In meetings, I sat as still as possible to avoid my mother’s glare, my legs dangling off the hard edge of the chair. I played with my mother’s fingers, bent them one by one as people took turns interpreting scripture. That way, I learned the Bible. I learned that we were not worthy, not a single one of us. I learned we were lower than worms, and we would hope to be better next week. At night, I chased fireflies, put them in jars, and made bracelets. I threw myself into piles of leaves in the fall; in winter, I stomped in the snow in red rubber boots and made snow angels, in summer, I learned to ride a bike, trying to keep up with my older sisters. We sang Tell Me the Story of Jesus and God is Faithful. My second sister never got over Sandy.

I learned we were lower than worms, and we would hope to be better next week.

On Saturday nights, my mother polished our shoes—every pair, from the baby’s to hers and my father’s—lining them up neatly on newspapers spread across the kitchen counters.

With the weekly laundry, she hung our clothes to dry outside in the summer or inside on racks in the winter. Once everything was dry, she folded the underwear, T-shirts, slips, towels, and sheets. One by one, using a Coca-Cola bottle filled with water, she sprinkled each piece of clothing, rolled it tightly, and placed it in a basket. Saturday afternoons, getting ready for meeting, she would unroll and iron our dresses and my father and brother’s shirts and slacks. The iron hissed and steamed, a soundtrack to her steadfast determination.

Saturdays also meant baths, shared in lukewarm water, one after another. My sisters and I put foam curlers in our ponytails, spraying them stiff with Aquanet. In our cult, a girl’s long, uncut hair was a sign of the spirit, as was modest dress and comportment. Scissors never touched my hair. Our clothes were handmade; our mother measured yards of material, laid and cut out patterns, pins clinched in her teeth. Her Singer hummed most nights. The comportment required earnest stifling of myself on my part. It helped that I was a good reader of the Bible. The grown-ups were impressed by my understanding. Surely, I would be a worker when I grew up.

Sunday mornings, our father read the Sunday comics while our mother ran in circles, yelling and handing out shoes as she tried to get all five of us kids ready for meeting. Flat back of the brush against our heads. Hold still. The contrast between the screaming and slapping before meeting and her saintly demeanor in meetings after would make good fodder for a sitcom. She slicked my hair straight back from my forehead with Dippity Do, sealing my compliance.

We didn’t believe in Christmas or television. Radios, too, were worldly and thus wicked. At annual church conventions held in farm country, the workers—what we called the preachers—sometimes broke the antennas off cars, ensuring no one could tune in. For entertainment, we played baseball in the cemetery or sang hymns. I cracked my head open once on a tombstone designated home base. Crabapple trees and lilacs in my backyard make me remember. The heavy weight of a good lilac blossom, the crabapples hitting my head. Falling into a trance.

In 1962, when I was nine, we moved to Northglenn, Colorado. Life magazine dubbed it "the most perfectly planned suburb in America." My parents bought one of its identical cracker-box homes, blond or red brick, all lined up in tidy rows like soldiers in formation. Ours was a red brick on the corner of Linda Sue and Leonard Lane, a picture of suburban perfection. We had a giant S, the first initial of our last name, on the garage door. Our lawn was trimmed. The backyard fenced. At school, we did nuclear drills. I grabbed my ankles and ducked under the now-modern Formica and aluminum desks in our classrooms. It seemed to me the wooden ones had been safer. The flag still hung; it flew dead center above Mrs. Branch’s desk, and we pledged our lives to God and our country. People dug fallout shelters in backyards, but we were God’s chosen people, and my parents felt no need. America the Beautiful would also prevail. But the flag was still there.

I hit puberty during the civil rights movement, the Vietnam War protests, and the burning of draft cards and bras era. I was taught what is now trending as tradwife values alongside witnessing Kent State and the assassinations of Martin, Bobby, and John. By then, my mother had gone to work nights as a Nurse’s Aid, and only the three younger kids still lived at home. She did all the domestic work, and we still attended church meetings as faithfully as ever. With his route sales jobs in the early morning hours, our father slept while we fended for ourselves.

And I'll take that ride again/And again/And again/And again/And again

By 1969, Northglenn’s reputation was tarnished. Reportedly, the suburbs had a drug problem. White flight didn’t work out so well. But everyone knew the real problems were in the cities. I started hitchhiking to downtown Denver with my buddies. Man landed a rocket on the moon—one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind. We lived in the greatest country in the world.

In 9th grade, I wrote a story about a white girl and a Black boy—a loose retelling of Romeo and Juliet. I learned about segregation, and when I took drinks at the water fountains in the school hallways, sometimes I cried. I wrote a passionate essay on behalf of what I imagined as Black people. I knew very few. By the time I saw Easy Rider at the drive-in movies, I was stoned on LSD.

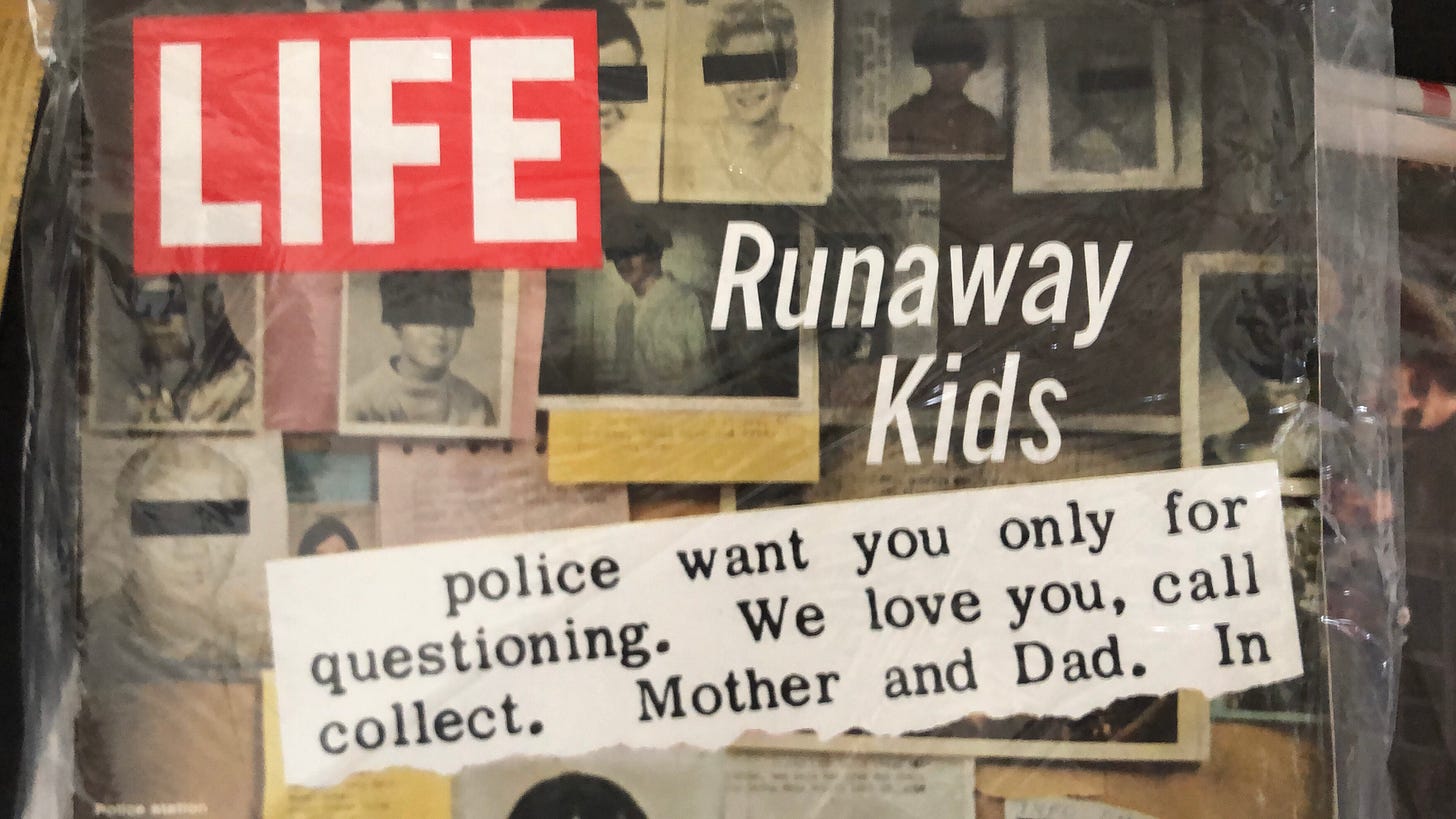

I started smoking Marlboros at fourteen, went to my first rock concert dressed in yellow and purple striped hip hugger bell bottoms, though I hardly remember seeing Johnny Winter and Fleetwood Mac; too many boys with Beatle hair were handing out Purple Microdot, Yellow Sunshine, and Windowpane. In the summer of ‘69, I ran away with an older guy, Maximillian Abdubuduwoski III, a Polish prince, to a commune in New Mexico, where he ditched me. I took more psychedelics and went wild in the streets with the rest of America’s runaway youth.

Turn on, tune in, drop out.

I thought I was anti-establishment, whatever that was. I became a teen mother at sixteen, descending from the security of working middle-class white privilege into the harsh reality of poverty. I never learned about feminism or classism in any school. Instead, I lived my way into it. I suspect that’s the way we learn.

It’s experience, not belief, that makes a difference.

Most of what I believe is kool aid.

Speaking of Kool-Aid, I’ve noted that if I develop a good conspiracy theory, I will likely attract thousands to my Substack.

This brings me to post-truth, which Oxford Dictionaries popularly defines as "relating to and denoting circumstances in which objective facts are less influential in shaping public opinion than appeals to emotion and personal belief.” Recently, I engaged (minimally) in a post claiming that vaccines, not COVID-19, are killing and disabling people.

I was awakened to iatrogenic harm through my own experience with a skiing injury twenty-five years ago. As a result, I became my own advocate and learned to question doctors’ advice and conclusions. However, due to growing up in an era where polio and smallpox were eradicated and vaccines normalized, where childhood disease was minimized (graveyards will show you that) and the mortality rate for children radically improved, my critically thought out conclusion regarding COVID vaccines was that the risk to me (age 70) of a mitigating vaccine is less than the risk of a COVID infection.

So accusing me of being brainwashed (drinking the Kool-aid), as those opposed are wont to do on some forums, for using my life experience to think critically doesn’t quite land. I’m open to the possibility this pandemic was manufactured to depopulate the planet, but I need more evidence. Since 2016, and especially since Tuesday, November 6, 2024, an entirely new layer of delusion and conditioning has unraveled for me. I suspect we all drank the Kool-Aid. Left or right. Red or blue. Black and white. All binaries are suspect. Social media has amplified and weaponized these divides, another construct we must dismantle.

The incursion of social media into our culture since the nineties means consensus reality has been decimated into fragments and bubbles.

We can no longer trust information. Is that a good or a bad thing? A gazillion narratives vie for domination. I resist drinking the Kool-Aid on either side and do my best to navigate the landscape based on my lifelong experience and coping skills.

Start with what you truly and most deeply know from critical thinking, direct experience, and the deepest recesses of your inner life. ~ Jim Palmer

I deconstructed the conditioning of my childhood and much of what I was taught. Still, this election taught me how much deeper I must dig into my beliefs and assumptions. Much deeper. Undeniably, I drank the Democratic Party’s Kool-Aid. I suspect I’m learning about democracy the same way I learned about feminism, classism, or any of the isms. By living through this moment in history.

Maybe that’s the assignment.

No one gets to define for us what it is to be American and that’s the most American truth of all.

Press the heart? ❤️🔥

On Repeat

"Highwomen"

I was a Highwoman

And a mother from my youth

For my children I did what I had to do

My family left Honduras when they killed the Sandinistas

We followed a coyote through the dust of Mexico

Every one of them except for me survived

And I am still alive

I was a healer

I was gifted as a girl

I laid hands upon the world

Someone saw me sleeping naked in the noon sun

I heard "witchcraft" in the whispers and I knew my time had come

The bastards hung me at the Salem gallows hill

But I am living still

I was a freedom rider

When we thought the South had won

Virginia in the spring of '61

I sat down on the Greyhound that was bound for Mississippi

My mother asked me if that ride was worth my life

And when the shots rang out I never heard the sound

But I am still around

And I'll take that ride again

And again And again And again And again

I was a preacher

My heart broke for all the world

But teaching was unrighteous for a girl

In the summer I was baptized in the mighty Colorado

In the winter I heard the hounds and I knew I had been found

And in my Savior's name, I laid my weapons down

But I am still around

We are The Highwomen

Singing stories still untold

We carry the sons you can only hold

We are the daughters of the silent generations

You sent our hearts to die alone in foreign nations

It may return to us as tiny drops of rain

But we will still remain

And we'll come back again and again and again

And again and again

And we'll come back again and again and again

And again and again

We'll come back again and again and again

And again and again

And we'll come back again and again and again

And again and again

One Thing

Having a 12-step practice is life-saving. It grounds me in the nature and truth of the human condition. It reminds me that belief is frequently delusional, fear-based, and erroneous. It helps me see myself in perspective.

I live on a beautiful planet spinning at the edge of the universe 13.8 billion years post big bang. All I need to do is find a dark night and gaze at the stars to remember I’m here. That’s enough.

There is no one true way. There’s only your way.

That’s why I’m inviting you to submit 500 words to thompsonk@substack.com about your experience on how to recover (from anything) find your badass, kick ass, and align with your true self for a special TNWWY feature.

What a beautiful thing to embody. ❤️🔥

Please consider supporting my writing and work at Substack. There will never be a paywall. I live in a different economy, one in which I give away to keep it. Sharing my work, commenting on it, and engaging with it are all beautiful ways to support my writing.

Consider me like your local NPR station and pledge a paid subscription.

Thanks for sticking with me. 🌻🫶🏻🌻

Shout Out

This week’s shout-out goes to Charli Mills’ Invitation to the Sacred Grove

Welcome to the Sacred Grove, a living writing project. Through dream tending and deep imagination, a writer explores the underworld of aging, illness, and what it means to live fully present to one’s beautiful, messy, painful, as-is life.

Charli’s way with words is admirable. Check her out.

Good work, Kelly! Recovery is real...it takes time, there's twist and turns and many switchbacks, and sometimes I lose my faith for a little while then reawaken to the truth that without connection to something greater than myself, I will not thrive, and so when I get knocked down, I may lick my wounds for a day or two or three, and then I kick myself gently in the ass, get back up and carry on. Self-forgiveness is essential! xoxo

I always find it interesting how many people don’t know the god bit was added in the 1950s. We’re a rather forgetful n bunch as a whole. And I know, I know, it’s by design, so much of the rewriting and washing out.

Another fabulous post, my friend. You’ve lived so much life. ♥️